Prairiewoods is currently exploring the characteristics of ecological spirituality, and we turn our focus to an examination of dualism versus non-dualism. First, what does dualism mean?

Prairiewoods is currently exploring the characteristics of ecological spirituality, and we turn our focus to an examination of dualism versus non-dualism. First, what does dualism mean?

Dualism (noun)

1. a theory that considers reality to consist of two irreducible (cannot be reduced or simplified) elements or modes

2. a doctrine that the universe is under the dominion of two opposing principles, one of which is good and the other evil

3. a view of human beings as constituted of two irreducible (cannot be reduced or simplified) elements (such as matter and spirit)—Merriam-Webster Dictionary online

According to Richard Rohr, dualistic thinking creates a system of false choices and too-simple contraries. Picture being in the chair at the eye doctor’s office and answering, “Which lens is clearer, 1 or 2?” That is dualism in its simplest form. We have been trained to choose “this or that.” Our world is locked onto dualism as a way of organizing ourselves and how we understand the “rules” of living. We humans seek safety in boundaries and certainties and often choose sides. Every generation has learned the painful lesson that little is certain in life and the “answers” are more complex than we had hoped. Ironically, leaning into non-dualism and a more expansive view is the antidote to division. The limitations of dualistic thinking “cannot process things like infinity, mystery, God, grace, suffering, sexuality, death or love” (Richard Rohr, Center for Action and Contemplation, Jan. 28, 2017). What if we employed a “wider lens” to the world?

What happens when we apply a dualistic mindset to ourselves? When we think of ourselves as separate containers of mind, body and spirit? We experience dissonance (inconsistencies between our beliefs and actions) and suffering. The truth is that we are an integrated and inseparable whole. We are a compilation of multiple dimensions that weave together uniquely in each person.

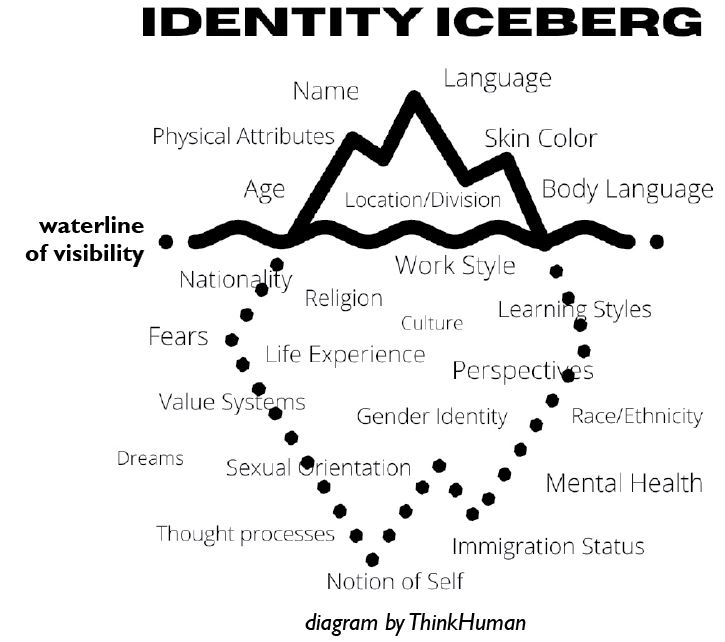

What happens when we separate people into groups? We create one-dimensional profiles of people when the truth of them is more beautiful, varied and complex. The iceberg of identity is often used in diversity training to help people move beyond the surface appearances of difference.

What happens when we separate people into groups? We create one-dimensional profiles of people when the truth of them is more beautiful, varied and complex. The iceberg of identity is often used in diversity training to help people move beyond the surface appearances of difference.

Looking at the iceberg, how many dimensions of your identify can you name? What might you learn if you explored these dimensions with others? Prairiewoods’ founders, Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, call us to be people committed to building bridges of relationship and celebrating unity in diversity. There is in all of us a yearning for belonging and connection. When we act on this and find opportunities to explore our points of intersection, it improves our sense of wellbeing. It reduces our sense of isolation.

“In a quantum universe, where everything is entangled, connectedness, not the clarity of separation, really matters.”

—Diarmuid O’Murchu, Ecological Spirituality, p. 4

How can we move away from segmentation and our tendency toward a scientific deconstruction of our world? We cannot exist without Earth and the other members of the ecosystem(s) of which we are a part. What if we change the word entangled, which sounds messy and uncomfortable, to enfolded. That word brings to mind a sense of embrace within the arms of all creation. That is the actual quality of our existence. Embraced and woven into the very fabric of life.

Ecological spirituality maintains that there can be no separation from the Creator. There is no sacred versus secular. The Creator spirit is part of the energy, the breath and the matter that forms us. So if our notions of separateness are in fact false, how can we “widen our lens”?

As individuals, we can deepen our practice of contemplation and mindful attention. Douglas E. Christie suggests that “the simple act of gazing, of paying attention—one of the most ancient and enduring ways of understanding contemplative practice—can open up a space in the soul, a space in which the world may live and move in us.”

Turning Toward vs. Turning on

There are numerous examples of people coming together to build bridges of relationship and celebrate human complexity. A Danish TV station created a video called “All We Share” several years ago to explore these unseen connections. The filmmakers brought together groups of people thought to be distinctly different from each other and asked simple questions, such as “Who among you is a stepparent?” “Who believes in life after death?” “Who is in love?” The results are surprising and inspiring. (Watch it at www.youtube.com/watch?v=jD8tjhVO1Tc&list=WL&index=1.)

Building bridges of relationship doesn’t have to be contentious. Nor does it require a film crew. We don’t have to start with the hard questions. The National Public Housing Museum created a toolkit called 36 Questions for Civic Love (www.nphm.org/civiclove). Participants take turns asking each other a series of questions. The design encourages sharing and, perhaps more importantly, listening with curiosity. Questions include “What’s your favorite kitchen smell?” and “Can you keep a plant alive?”

This is another rich example of people working on ways for us to connect and belong to each other versus creating separation and isolation. In every case, the transformation and healing are the result of compassionate and curious questions that arise from within every individual. A loving, compassionate gaze. This gift is first given to us by our Creator, which we in turn are called to share with each other. What will be possible when we seek to know versus categorize, convert or condemn? This shift will help us to make great strides toward a resilient, creative and hopeful unity.

—Leslie Wright, Prairiewoods director