“Witches can be right; giants can be good” (lyrics from “No One is Alone,” from the Sondheim-Lapine musical “Into the Woods,” 1986). What? We don’t often think of notorious archetypes of evil as fonts of truth or dispensers of reality and goodness. Morality and ego-development are so much easier when our “witches” are bad, and our “giants” are worthy of only derision and being slain, no matter what is stolen from them and whose family members we kill. What happens when the edges are blurred between perception and reality of someone’s “truer” and “fuller” self?

“Witches can be right; giants can be good” (lyrics from “No One is Alone,” from the Sondheim-Lapine musical “Into the Woods,” 1986). What? We don’t often think of notorious archetypes of evil as fonts of truth or dispensers of reality and goodness. Morality and ego-development are so much easier when our “witches” are bad, and our “giants” are worthy of only derision and being slain, no matter what is stolen from them and whose family members we kill. What happens when the edges are blurred between perception and reality of someone’s “truer” and “fuller” self?

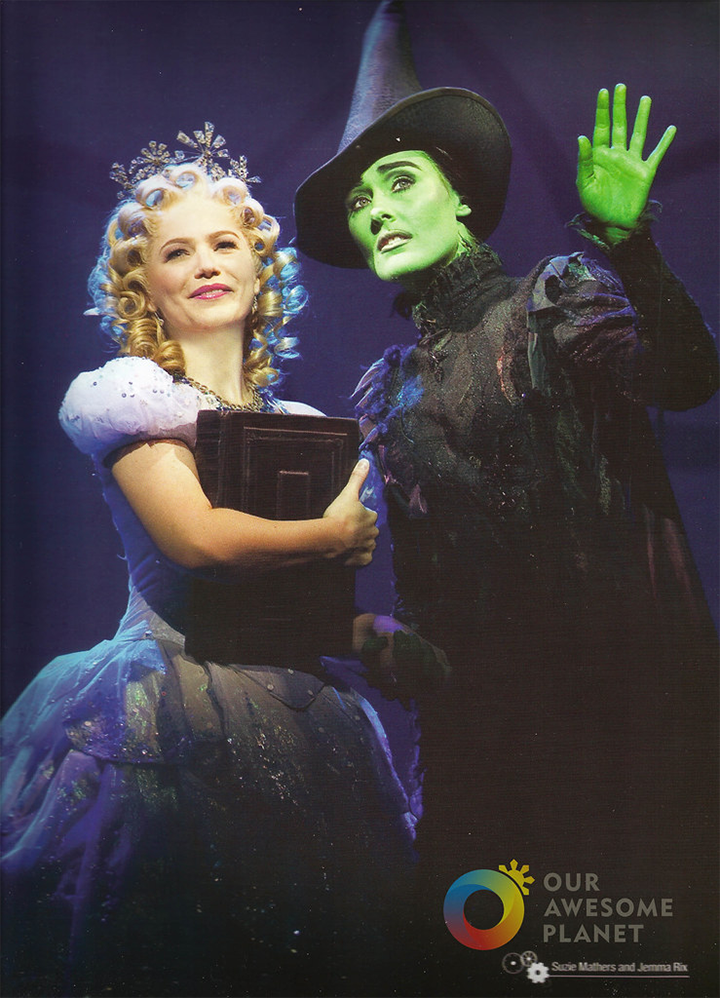

Gregory Maguire’s 1995 book, Wicked, turned Frank L. Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz on its head when he provided “background” for the witches from the land of Oz. For example, Elphaba, the so-called “wicked” witch of the adapted story Wicked is actually a champion of social justice whose moral fiber costs her her life’s reputation, while Glinda, the so-called “good” witch from Baum’s original story, is a shallow sycophant who must learn authenticity and moral character as she develops in her relationship with Elphaba: “So much of me is made of what I learned from you” (lyrics from “For Good,” from the Stephen Schwartz–Winnie Holzman musical “Wicked,” 2003). The two are not simplistic literary foils, but intertwined facets of a whole, whose relationship mirrors the fuller sense of who we all are, complex, contradictory creatures of mystery, capable of enormous courage and wisdom in the depths of our antipathy and fear.

We long for authenticity in self-expression, in relationships and in our soulful odysseys. The spiritual life requires it. “Authenticity is not something we have or don’t have. It’s a practice—a conscious choice of how we want to live. Authenticity is actually a collection of choices, choices that we make every day. It’s the choice to show up and be real. The choice to be honest. The choice to let our true selves be seen” (Brené Brown, The Gifts of Imperfection).

We long for authenticity in self-expression, in relationships and in our soulful odysseys. The spiritual life requires it. “Authenticity is not something we have or don’t have. It’s a practice—a conscious choice of how we want to live. Authenticity is actually a collection of choices, choices that we make every day. It’s the choice to show up and be real. The choice to be honest. The choice to let our true selves be seen” (Brené Brown, The Gifts of Imperfection).

We long to dispel illusion and delve deeply into the real. Philosophers have long wrestled with three perennial conundrums that dance around the edges of our awareness: 1) The One and the many; 2) constancy and change; 3) illusion and reality. Generally, most philosophical dilemmas, whether ethical, socio-political or existential issues, tap into one of these rudimentary ideas at a profound level. The third one—illusion and reality—is especially germane in a Covid-ridden world plagued by misinformation. Ours is a world in which virtual—and viral—illusion, and deliberate deception for political or financial gain, or a bid for ultimate power is made over and against the wider “We.” Trust becomes the most dangerous game as we experience gaps in perception and reality. Doubt sets in and feelings of betrayal emerge. And the spiritual sojourner turns to self-reflection: Who are we, really, without our masks, without our public personas, our concealers or our pretend-selves?

As we watched U.S. Olympic gymnast Simone Biles struggle with the “twisties” at the Tokyo Olympics, there were those who questioned her perceived reality, i.e., her insistence that her body was not in sync with her own perception, and that the consequences of performing in this compromised state was not only inadvisable for the team’s bid for a medal, but dangerous—possibly disastrous for her own physical and mental health. As she withdrew from event after event at the Olympics, her detractors questioned the gymnast’s courage, determination, mental toughness and especially her integrity, even while dozens of gymnasts and other world-class athletes attested to the mental toll of high-pressure performance sports, confirming from their own experience that Simone’s bout with severe disorientation was both real and hazardous. She risked telling her fuller truth—and the ensuing firestorm of castigation from her detractors—by removing the false persona of the premier gymnast “gutting through it at all costs to win a gold medal.”

Who can know the fullness of anyone’s truth, anyone’s fullest reality? Can we ourselves even know the fullness of our own authentic selves, especially when that knowledge keeps us from feeling like we belong? Spiritual author Mateo Sol maintains that the process of “domestication” sets in about age 3, when our authentic selves begin surrendering to our significant, formative community’s expectations/corrections/affirmations of our behaviors as benchmarks for inclusion and acceptance or ostracization and punishment (https://lonerwolf.com/authentic-self/). “This new self-worth system forces us to change. It forces us to create a false image of ourselves, a dream. Slowly we begin to notice that different people expect different things from us—our parents, our teachers, our friends, our priests, our bosses, our siblings, our lovers all want something specific from us—and so we are split up into dozens of different versions of ourselves. We become so good at living up to these different images of ourselves that we forget who we really are.” Eventually, there arises a gap—and sometimes an interior conflict—between authenticity and belonging. Spiritual author Fiona English writes, “Authenticity requires us to reveal the most vulnerable parts of ourselves to others. The parts we value the most are the parts we hide. Because authenticity carries risk. That risk sits in the aspect of authenticity which is rarely spoken about. The relational aspect. Being my true self requires me to show myself to others. And with that, there is a risk that you will reject some part of me. What I have learnt is authenticity and belonging are often in conflict. To nurture our authenticity, we must sacrifice belonging” (https://medium.com/@FionaEnglish1/the-compromise-between-authenticity-and-belonging-d6f669c002a6).

And, there’s a twist: What often emerges in the context of struggle between authenticity and belonging is—ironically—the attempt to create separation within the whole. Perhaps by wearing masks, feigning separateness with the use of titles or hierarchical distinctions, or by a presumed posture of being “outside and above” the fray, we want to distinguish ourselves within the community. It’s both. We desperately desire belonging AND our own specialness/distinction within the same community. We are quite creative in our construction and wearing of our masks to maintain our sense of our position in a community, especially if that position guarantees our specialness or our superiority over others. The way we maintain the facade is in a million little details of our daily behavior and interaction, and floats somewhere between rehearsed rhetoric used to manipulate others to “respect” our position over them or outside the whole, and consummate self-deception that we are only thinking and behaving this way for the good of the whole. It’s an illusion worthy of the Emperor’s new clothes.

In the Sondheim-Lapine musical “Into the Woods,” the sarcastic, ugly-turned-voluptuous Witch known for casting curses and imprisoning her innocent—and abducted—“child,” sings her truth at her “last midnight,” when confronted with other characters’ hypocrisy. “You’re not good; you’re not bad,” the Witch laments, as the characters all attempt to shift blame to one another while remaining in the coveted good graces of the community. “You’re just nice” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aasECsxrSzQ). Many of us are taught to be “nice” rather than authentic. We are taught to conceal our ugly crying, our pain, our vulnerability, our anger, our resentment, even our interior struggles and our deepest fears and questions in order to remain outside the fray of human vulnerability. Vulnerability is meant to be hidden in a culture that prizes rugged individualism, self-sufficiency and insuperability above all. “We’re #1!” And by that we mean we stand alone, apart, above, separate, atop the heap. The illusion is that we are separate from others and all creation. If we operate under this inherited delusion that we are here to subdue or dominate or stand apart from the whole, rather than live into the web of life, we can allay our fears with the seduction of promised invulnerability. We think we won’t be susceptible to the pain that accompanies our ontological poverty. At the very least we don’t want to appear to suffer the same pedestrian fears, struggling with our shadows, suffering and experiencing raw vulnerability as our fellow creatures do.

In the Sondheim-Lapine musical “Into the Woods,” the sarcastic, ugly-turned-voluptuous Witch known for casting curses and imprisoning her innocent—and abducted—“child,” sings her truth at her “last midnight,” when confronted with other characters’ hypocrisy. “You’re not good; you’re not bad,” the Witch laments, as the characters all attempt to shift blame to one another while remaining in the coveted good graces of the community. “You’re just nice” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aasECsxrSzQ). Many of us are taught to be “nice” rather than authentic. We are taught to conceal our ugly crying, our pain, our vulnerability, our anger, our resentment, even our interior struggles and our deepest fears and questions in order to remain outside the fray of human vulnerability. Vulnerability is meant to be hidden in a culture that prizes rugged individualism, self-sufficiency and insuperability above all. “We’re #1!” And by that we mean we stand alone, apart, above, separate, atop the heap. The illusion is that we are separate from others and all creation. If we operate under this inherited delusion that we are here to subdue or dominate or stand apart from the whole, rather than live into the web of life, we can allay our fears with the seduction of promised invulnerability. We think we won’t be susceptible to the pain that accompanies our ontological poverty. At the very least we don’t want to appear to suffer the same pedestrian fears, struggling with our shadows, suffering and experiencing raw vulnerability as our fellow creatures do.

Authenticity requires us to relinquish control of perception and live into our fuller selves as human-merely-beings, and into the fullness of our own vulnerability and fear, even as we strive to develop our sense of courage and self-possession. As leaders, counselors, educators, health care professionals or even spiritual guides might admit, their public-facing personas might involve adopting “masks” that allow them to serve/attend/minister to their students/clients/patients/spiritual companions without projecting their own questions/fears/struggles onto them. This distanciation requires constant shadow-work and self-reflection. A retired educator reflects, “I justified possessing both a private and public persona by suggesting that it was, in fact, necessary to have both; that it would not be appropriate to bare your soul to people you minister to. That might engender insecurity, unnecessary doubt and even chaos in the faith community. So, I thought, it was perfectly normal to be on a personal growth trajectory while at the same time saying only those things that were ‘acceptable’ for public consumption” (https://www.mysteinbach.ca/blogs/8887/authenticity-and-spirituality/). Juggling the multi-persona masks can lead to some dissonance, the author suspects, and to devastating consequences. “It seems to me, that if one stays within this duality too long the dissonance between these two personas can become unbearable. A homesickness develops; a desire to just be who you are and let the chips fall where they may.”

Sometimes we protect ourselves and our position within the community by remaining behind our masks. As many wear respiratory masks today to protect others and themselves from Covid transmission, the metaphorical masks we are wearing need to fall away for us to relate authentically. Not everyone will be privy to our innermost, fullest, authentic selves—nor would it be advisable. Intimacy is reserved for those with whom we trust our most vulnerable selves. However, being honest and fully who we are with our own selves is a must. At the very least, we owe a debt of transparency and legitimate authentic revelation to balance our desire for perceived perfection. We are “human-merely-being” (ee cummings), struggling to breathe into our truth, crying from our depths, loving fiercely and failing miserably like every other human being. We are eminently worth being perceived as we truly are, unable to make sense of our own paradoxes, flawed, frightened of being unwanted and unloved, and hopelessly inconsistent. Also, we are thoroughly loveable and immeasurably precious, as unbearably irresistible as a new fawn learning to walk on all fours, or a newborn human completely incapable of survival on her/his own, but able to enthrall an entire community with one adorable “coo.”

So, the question becomes where, how and with whom can we be truly ourselves, truly at home, most fully real and unapologetically so? Do we allow ourselves to be unmasked from our pretend selves even when there’s no one around? Our trusted companions and friends recognize our authentic selves because they will call us on our fake personas, disabuse us of our airs of perfection or superiority. And we can let go of the pretenses and masks we have adopted to maintain public perception and hard-fought egoic development. It is when we are most vulnerable, in moments of paralyzing fear or confusion, failure or doubt, that the masks fall away and we reveal to ourselves—and to those privileged to companion us—who we truly are. Yes, we are fallible, fearful, confused, as well as heartily open with arms spread wide, needing embrace, needing self-expression that is not constrictive, but evolutionary, perhaps even revolutionary. We can just be ourselves—our trusting, courageous, hopeful, terrified, anxious, thoroughly unglued, fantastically creative and undeniably mysterious selves. Maybe take a peek and see. Just be you.

—Laura Weber, Prairiewoods associate director and retreats coordinator